Rapture Read online

RAPTURE

RUSSIAN LIBRARY

The Russian Library at Columbia University Press publishes an expansive selection of Russian literature in English translation, concentrating on works previously unavailable in English and those ripe for new translations. Works of premodern, modern, and contemporary literature are featured, including recent writing. The series seeks to demonstrate the breadth, surprising variety, and global importance of the Russian literary tradition and includes not only novels but also short stories, plays, poetry, memoirs, creative nonfiction, and works of mixed or fluid genre.

Editorial Board:

Vsevolod Bagno

Dmitry Bak

Rosamund Bartlett

Caryl Emerson

Peter B. Kaufman

Mark Lipovetsky

Oliver Ready

Stephanie Sandler

Between Dog and Wolf by Sasha Sokolov, translated by Alexander Boguslawski

Strolls with Pushkin by Andrei Sinyavsky, translated by Catharine Theimer Nepomnyashchy and Slava I. Yastremski

Fourteen Little Red Huts and Other Plays by Andrei Platonov, translated by Robert Chandler, Jesse Irwin, and Susan Larsen

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Published with the support of Read Russia, Inc., and the Institute of Literary Translation, Russia

Translation copyright © 2017 Thomas J. Kitson

All rights reserved

EISBN: 978-0-231-54329-3

Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-231-18082-5 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-231-18083-2 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-54329-3 (electronic)

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at [email protected].

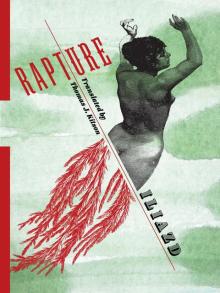

Cover design: Roberto de Vicq de Cumptich

Book design: Lisa Hamm

CONTENTS

Introduction: The Golden Excrement of the Avant-Garde

Rapture

01

02

03

04

05

06

07

08

09

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Notes

INTRODUCTION

The Golden Excrement of the Avant-Garde

PRELUDE

In the years before Iliazd’s death in 1975, he could be seen strolling through Paris’s Latin Quarter, wearing a Caucasian sheepskin coat and holding a shepherd’s staff. An unusual flock surrounded him—the thirty or so cats that lived in his two-room studio. By then, he had become France’s most revered publisher of the livre d’artiste (artist’s book), working regularly with Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Max Ernst, and Joan Miró. His mysterious ability to herd cats probably reflected the strength of an artistic vision that could integrate such original talents into books that were always, ultimately, “by Iliazd.” But one suspects that he also identified so closely with his cats for their nine lives, their mythical ability to survive catastrophe and land on their feet, as he had more than once.

Rapture emerged from an earlier exile’s life in Paris, virtually unknown to the collectors who treasure Iliazd’s artistic editions. It is a testament to the survivor’s ability to reckon up and move on, the reformulation of an artistic credo adopted during an even earlier life lived under another name among Russian avant-garde poets and painters. Iliazd shared with his friend Picasso a deep faith in the artist’s restlessness and the need to undergo transformation, but he also trusted the power of time to transform artistic objects. “A poet’s best fate is to be forgotten” in the expectation of rediscovery by new enthusiasts and interpreters. Rapture is such a neglected treasure.

The great works of avant-garde modernism usually arrived with a bang. Their scandals—whether in the theater, like Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Rex, or the courtroom, like Joyce’s Ulysses—have become integral to the way we think about them. Iliazd was no stranger to scandal. In fact, for a time, his reputation in Russia was based on nothing more than his outrageous lectures and manifestos. Russians even today think first of his “extreme” experimental dramas written and published during the Russian Civil War. When Iliazd (then still known as Ilia Zdanevich) left the former Russian Empire, he fell effortlessly into the scandalous last Paris Dada soirées, where the tactic of shocking the bourgeois had become routine and the Surrealist movement announced itself in violent attacks on the stage.

Rapture did not arrive this way in March 1930. Nor did it meet the eager, protracted anticipation Joyce was able to muster for his work in progress before its final advent as Finnegans Wake. It was ignored. The unassuming yellow-green book, published at Iliazd’s own expense, went on sale in only one Paris bookstore with a long history of supporting the new art. Within several days, Iliazd had inserted strips of paper into unsold copies with the challenge: “Russian booksellers refuse to sell this book. If you’re that inhibited, don’t read it!” Obviously, this was not exactly the usual bang, but it was hardly Eliot’s “whimper.”

A world, nevertheless, had ended with the displacements brought on by the 1917 Russian Revolutions. Iliazd had passed, like so many refugees in the aftermath of the First World War, through the chaos of postwar Istanbul and now found himself not just in exile, but even on the margin of the Russian emigré community in Paris. He was cut off from his former associates and not yet fully engaged with the French artists who would become so important to him later. He envisioned Rapture, his first published work of prose fiction, as a final statement on his former life, already delivered with confident hope from inside a new life that was still taking shape.

By coincidence, within weeks of Rapture’s unremarked release, news of an all-too-final bang reached Iliazd: Vladimir Mayakovsky, the star of the Russian avant-garde, had shot himself through the heart on April 14, 1930, sending a spectacular signal that the old life had indeed come to an end.1 Mayakovsky’s lament that “the love boat broke up on daily routine” expressed his inability to imagine himself outside the heroic public role of the revolutionary artist. Art should be for life’s sake, but his heroism had failed to transform the conditions of everyday life. Iliazd still believed in “life for art’s sake,” and his belief allowed him to continue his work unnoticed, to enter a period that looked like dormancy, and to emerge quietly, catlike, in a new guise.2

1.

On the surface, Rapture takes the form of an adventure novel about Laurence, a treasure-mad young bandit. It tells the story of his doomed love for the mysterious beauty Ivlita and recounts how Laurence establishes a reign of terror over several mountain villages. He then departs with his gang on a series of forays down to the flatlands and the provincial capital, drawn into schemes promising ever larger prizes that turn out to be ever more elusive and evanescent. Laurence leaves a trail of victims and eventually finds himself pursued by government authorities, abandoned by his comrades, and hiding with a pregnant Ivlita in a cave. Finally, Ivlita, too, betrays him. Shortly after being imprisoned, he breaks out with the help of some nameless admirers and sets off to avenge himself on Ivlita. He arrives just in time to see Ivlita die giving birth to their stillborn child, and he succumbs to death beside them.

The story is energetic and fast-paced, as the Russian critic D. S. Mirsky noted in a short French-language review not long after Rapture’s publication. It bears a quality perceived at the time as “cinematic.”3 But while the story may be engaging for its own sake, Iliazd is playing a game of concealment and revelation with treasure-s

eeking readers. What should we make of the murdered onanist monk who sees satyrs gnawing rifle barrels, as though they were imitating the poet in Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell? Why do we find among Ivlita’s neighbors a goitrous (or wenny) family with fourteen children ranging in age from four to sixty divided into “toiling” and “spoiled” classes and a second family of cretins who live in a stable and emerge in the evening to sing unpronounceable, incomprehensible songs? And why has Ivlita’s father, a grieving retired forestry official who philosophizes and collects books in languages he can’t read, built such a fancifully carved mahogany house? Why, further, does he fail to distinguish his daughter from his dead wife? Rapture represents, as I noted above, Iliazd’s reckoning with the Russian avant-garde. He is settling accounts with personalities (including himself), evaluating themes and techniques by mixing allegory and roman à clef, but passing them through the Freudian dream work of condensation and displacement. In order to begin to see how, we need a somewhat longer history of the furiously creative movement known as Russian Futurism and Ilia Zdanevich’s place in it.4

Ilia Mikhailovich Zdanevich was born in Tiflis (modern Tbilisi), the capital of the Georgian province of the Russian Empire, on April 21, 1894.5 His father, a teacher of French, came from a Polish family that had been exiled to the area after the Polish uprising of 1830. His mother was a cultured Georgian woman, a former student of Tchaikovsky, and kept her home open to Tiflis’s artistic and intellectual elite. She also greatly desired a daughter, and in the mythology he later constructed for himself, Zdanevich made much of being treated as a girl well into his childhood.

Zdanevich’s father kept track of news from France, and since the family was curious about artistic trends in particular, Zdanevich learned of F. T. Marinetti’s 1909 “Manifesto of Futurism” not long after it appeared in Le Figaro. Zdanevich was already writing poetry in imitation of Russian Symbolists like the sun-worshipping Konstantin Balmont, and quickly became fascinated with Marinetti’s antisentimental shift in values. Solar worship quickly yielded to vehement attacks on the sun in the spirit of Marinetti’s “Let’s Murder the Moonlight.” Zdanevich asked his father to translate Marinetti’s manifestos so he could study them more closely.

Although Zdanevich was far from the capital, St. Petersburg, as he learned about Marinetti’s Futurism, he would have read in the leading artistic journals about what soon became known as “the crisis of Symbolism,” the reigning school of poetry in Russia during the first decade of the twentieth century. Symbolism was roughly aligned in the visual arts with the post-Impressionist aestheticism of the World of Art movement, perhaps best known in Western Europe and America for its impresario, Serge Diaghilev, and his Ballets Russes. Zdanevich’s erstwhile favorite, Balmont, belonged, along with Valery Briusov, to an older generation of Decadents who had imbibed the themes and techniques of French poetry from Baudelaire on. More recently, a younger generation of Symbolist poets (Viacheslav Ivanov, Alexander Blok, and Andrei Bely) had immersed themselves in the experience of a mystical world soul associated with the Goethean Ewig-weibliche and the philosopher Vladimir Solovyov’s writings on Sophia, the Wisdom of God. Their explorations, building on the “musical” invention of the Decadent generation of Symbolists, inspired an unprecedented wave of linguistic experimentation—always in the service of some other goal. Ivanov, for instance, a Nietzschean specialist on the interplay of Dionysius and Apollo in the Greek sources, characterized poetry as a vehicle a realibus ad realiora. As a result, younger poets began to sense that, for all his technical brilliance, Ivanov was not interested in “the word as such.” Poets within Ivanov’s circle had already turned to primitivism as an antidote to the cold sheen of civilization. They were also experimenting with folk arts to extract a new mythology and devise accompanying theatrical rites that would reestablish solidarity in modern society. Futurism, not just for Zdanevich, provided an opportunity to focus on the tools of poetry while mocking all of these “higher” goals.

Several factions of younger poets and artists rose up to challenge their elders, who were also in many cases their teachers. Primitivism flourished, but its practitioners largely discounted the mystical search for the essence of the people in favor of examining formal technique. Where such mysticism survived (in the work of the poet Velimir Khlebnikov, for instance), it tended to be grounded in minute studies of dialect and etymology, in the specific nuances of word roots and variants. Poets began to talk about the “thingness” of words and of poetry as a craft. Among them, the Acmeists (Nikolai Gumilev, Anna Akhmatova, and Osip Mandelshtam) formed the Poets’ Guild as an alternative to Ivanov’s more exalted Academy of Poetry. Khlebnikov, who insisted on using only Slavic words, devised the term “budetliane” (people of the future) in 1910 to describe a group of poets and artists that would eventually include Mayakovsky and take on other names (Hylaea, Cubo-Futurists).6 He deepened his idiosyncratic research into the roots of Slavic languages and, together with Aleksei Kruchenykh, arrived at some of the most radical treatments of the word as material for analysis and resynthesis. Another group of poets called themselves Ego-Futurists, after Igor Severianin’s 1911 manifesto. Their belief that poetry should express unbridled subjectivity rather than mythologizing and moralizing justified yet more experiments in neologism.

Futurism, it should be said, came to Russia not just through verbal art, but also through the painting and sculpture of Marinetti’s compatriots, Umberto Boccioni, Gino Severini, Carlo Carrà, and Luigi Russolo, as well as through Picasso’s application of Futurist techniques to some of his Cubist work. Because Futurism was subsequently adopted and adapted through so many channels by Russian artists and writers, it never became a unified movement with an acknowledged leader. Consequently, squabbles over priority arose almost at once among those who first appropriated the name in Russia.

When Zdanevich arrived in St. Petersburg in 1911 to study law at the university, his brother, Kirill, acquainted him with a group of young painters calling themselves the Ass’s Tail, gathered around Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova. These artists were feverishly assimilating and transforming styles and techniques drawn both from their Western European counterparts and from Russian folk artifacts, religious icons, and popular printed sheets (lubki). Larionov apparently found the eloquent Zdanevich useful as a spokesperson for his particular brand of Futurism. The still-teenaged Zdanevich spent the first year of his public life as a Futurist primarily cowriting manifestos with Larionov, presenting polemical lectures, and participating in open disputes.

According to Zdanevich, he was the first to proclaim the name Futurist in Russia when he took the stage during a debate over painting styles hosted by the Union of Youth in St. Petersburg on January 12, 1912. In contrast to Khlebnikov’s impulse to “slavicize” the movement, Zdanevich tended, at first, to faithfully reproduce all the characteristics of Marinetti’s stance, down to his own vocabulary and rhetoric, often quoting directly from Marinetti’s manifestos. Nevertheless, as he became more accustomed to the theatricality of public speaking, Zdanevich rapidly developed his own way of mixing Marinetti into homegrown Russian debates on aesthetics. In his lecture “On Futurism,” delivered in Moscow on March 23, 1913, to coincide with Larionov and Goncharova’s Target exhibition, he combined the hoary Russian materialist claim that a pair of boots is worth more than Pushkin with Marinetti’s pronouncement that “a roaring car…is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”7 He goaded his audience by waving an American Vera brand shoe, claiming that it was more beautiful than the Venus de Milo because of its ability to separate human beings from the earth and raise them out of the muck. His lecture ended, as he fully intended, in a scandal, with the audience attacking Zdanevich, who defended himself with tea glasses and a large platter. He ended up forfeiting his speaking fees to cover damage to the theater—but in compensation he had suddenly become famous in his own right.

Audiences witnessed the corollary to Zdanevich’s act a year later when he held forth

on “Shoe Worship” at the Stray Dog Cabaret, the center of Petersburg bohemia, on April 17, 1914. In this parody of Symbolist mythmaking, delivered while Zdanevich pretended to sleep on stage, he wove a complicated panegyric to shoeshine men, the priests of the shoe cult. Their “holy hands, black and grimy from polish, turn your shoes into mirrors that amusingly reflect the sky.”8 In transforming the instruments that raise human bodies from the earth so that they also reveal the sky to human minds, the shoeshine men selflessly bring about the end of their own usefulness by preparing human beings for their next advance: joining the French aviation pioneer Louis Blériot to live in the air, where shoes need no longer be worn. Zdanevich displaced Marinetti’s overly luxurious machine fetish with a mass-produced object like those worn by every member of his audience (and an object, besides, of Freudian fetish). Iliazd’s parodic treatments in Rapture of Symbolist themes and their Marinettian Futurist negations (“scorn for woman,” “murdering the moonlight,” “wireless imagination,” “rootless humans”) follow the same pattern by making images and metaphors concrete while widening as far as possible their circles of connotation, multiplying the levels of meaningful resonance they generate.

Most of Zdanevich’s writing up to this point, as it happens, addressed problems of visual art rather than poetry, but he was beginning to assess what the various Futurist poets had accomplished. When his mother begged him early on not to subject himself to the shame of public scandal, he assured her that he was biding his time, hoping to trade on his notoriety in order to advance his own ideas about poetry in the future.9 He had begun experimenting with verbal forms analogous to the Rayonist abstraction Larionov was promoting at the time. Only now did he feel he was ready to move beyond the derivative poetry of his early notebooks.

Rapture

Rapture